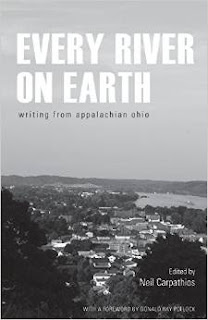

I was first sucked into Maggie Boylan's chaotic world in the collection entitled Every River on Earth, an anthology of Appalachian writers from southwestern Ohio. In that story, then entitled "Coming Home," Maggie had just completed her court-ordered rehab and was struggling to navigate the pitfalls of being labeled a known drug user who must steer clear of all other known drug users or be tossed back in jail. To complicate matters, most of Maggie's neighbors are dealers, users, or cops, her husband has given up on her, plus she has no ride. That hair-raising story in which Maggie must run a physical and spiritual gauntlet to maintain even one day of sobriety post-rehab made me want to root for Michael Henson's foul-mouthed protagonist. If she is not an Everywoman, she is surely a familiar face in the undeniable scourge that is prescription drug abuse.

I was first sucked into Maggie Boylan's chaotic world in the collection entitled Every River on Earth, an anthology of Appalachian writers from southwestern Ohio. In that story, then entitled "Coming Home," Maggie had just completed her court-ordered rehab and was struggling to navigate the pitfalls of being labeled a known drug user who must steer clear of all other known drug users or be tossed back in jail. To complicate matters, most of Maggie's neighbors are dealers, users, or cops, her husband has given up on her, plus she has no ride. That hair-raising story in which Maggie must run a physical and spiritual gauntlet to maintain even one day of sobriety post-rehab made me want to root for Michael Henson's foul-mouthed protagonist. If she is not an Everywoman, she is surely a familiar face in the undeniable scourge that is prescription drug abuse.

The Way the World Is: the Maggie Boylan Stories is Michael Henson's latest book from Brighthorse Books, 2015. He already has an impressive array of publications in poetry and fiction with seven other works in print since 1980 from West End Press, MotesBooks, and Dos Madres Press, to name a few. He is also a long time member of the Southern Appalachian Writers' Cooperative. Add to his accolades that The Way the World Is has earned him the Brighthorse Prize in Fiction for 2014 and that he has been declared by official decree the Poet Laureate of Mt. Washington. I think I would cherish that honor the most. Being recognized as someone important to one's own community speaks volumes about Henson's impact as a writer, a community organizer, and a substance abuse counselor.

But back to the compelling character Henson has created in this collection of linked stories, Maggie Boylan. Described on the back cover as "Addict, thief, liar, lover, loser, hustler…queen of invective," the reader sees Maggie struggling to navigate the labyrinth of traps addiction sets for its snares. In one story, Maggie gets her hands on ten dollars which she attempts to bring to her long-suffering husband, Gary, who sits in jail for something she has done, taking the proverbial "rap" for her. Yet, at every turn, former drug buddies are waiting to get that quivering bill from her addled and aching fingers. The cycle continues.

The stories can all stand alone, of course, but they are arranged skillfully in an order that delivers dramatic tension and the satisfying feeling of having read a short novel. In addition to Maggie, we meet deputies who battle with the shadowy cast of characters on Pillhead Hill, many of whom they have known since elementary school, reformed druggies who lend a hand to the wavering Maggie, judges who are part of the problem, and a couple of drug-doomed young women Maggie will alternately hustle, help, and then grieve.

The cover art for the collection was done by folk artist Bonita Skaggs-Parsons, preserved in stark photograph by her daughter, Misty Skaggs. The tough questions raised for the reader by The Way the World Is include what can we do now that heroin is part of the picture? How can we turn away from someone so real and in our faces as Maggie? Here is one passage showing Maggie's fight for sobriety:

"it would be just a short walk down her lane and across the road, over the bridge, and up that Pillhead Hill to the house. The lights would be on and the boys would be happy to see her. And of course, they would front her--one or two, or even three or four--enough to get her through this godawful night.

Without willing it or willing against it, she threw the little jacket across her shoulders and stepped into the yard. Without willing it or willing against it, she crossed the yard. At the edge of the road she stopped, out of old habit, and looked to the right and to the left.

Then when she looked forward again, she saw the coyote in the road. He had not been there when she looked to the right; he had not been there when she looked to the left, but now, as she looked to cross the road, the coyote stood directly in her path. He must have come up from the bed of the creek, she thought. As if in response to the notion, the coyote shook out his coat and cast a silvery spray into the moonlight. Maggie stood frozen in place."

This review first aired on WVXU.org's AROUND CINCINNATI in May, 2015. To listen to the audio clip of the review, click here.