Early Farming Woman—August/September

Early Farming Woman—August/September

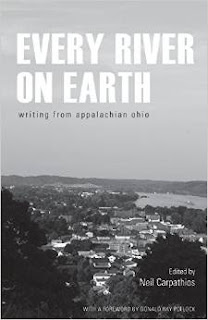

I first discovered Jeanne Bryner’s poetry in a compilation called Every River on Earth, a rich anthology of Appalachian writers from Ohio University Press. Her poems in that collection focused in close on the good people who work the land. In her recent chapbook from Finishing Line Press entitled Early Farming Woman, she again trains her poet’s eye and ear on those people, but the reader is teleported back to the earliest farmers in a time when young virgins are sacrificed for the harvest, a nomad woman must decide to abandon one child to save the rest of her brood, and violent raids are common to acquire or defend the best land. The images are brutal, yet beautiful, as the women of the poems braid communal bonds of sisterhood required to nurture life against the beginnings of war.

Many anthropologists believe that war—as we know it—did not exist as long as humans were hunter-gatherers. These scholars theorize that wars developed as humans began to claim territory for farming. The competition for fertile land gave rise to open conflict. In the expert sequencing of her poems, Bryner’s first poem “carves the moment:

quiet hummingbird, wren golden eagle,

the milk rising, the water running down.”

The reader moves from bucolic bliss of women bathing at water’s edge, one sister carving the image of the moment, to the first major conflict in the series of poems. We journey through a land and time fraught with dangers and loyalties, heartbreak and joy.

I first read the 18 poems out of sequence, favoring titles I found intriguing. While the poems stand alone quite well—and many of them were submitted as stand alone for previous publication in various journals—I really didn’t get the full effect of the chapbook’s artfulness until I read it in sequence. Bryner has mastered placing her poems in a way that surprises and shocks the reader with story. I think I audibly gasped a few times during my second reading at the horror or the anguish or the compassion of the speaker.

All viewpoints within the chapbook are distinctly feminine. Whether it be the new mother bathing at the stream with her new baby, flanked by her mother, who is lovingly washing her daughter’s hair while a new generation suckles, and a sister who is documenting the beauty of the moment, her female relatives, and nature in a carving. Or whether it be a female lamb who is adopted as both a pet and a breeder by an early farming family. The lamb describes the heavy bonds of love in these haunting lines:

“…The children grew,

swinging clubs, pelting rocks, a sudden thud

I was blinded. Now if the great door stands open,

I don’t try to leave. Protection is milk,

and love a brand,

not nearly as gentle as it sounds.”

The title poem, placed nearly one-third of the way through the chapbook, “Early Farming Woman,” portrays a widow trying to fend for her family when she happens upon a dark-skinned man with a lamb slung over his shoulders. The widow considers her plight and the promise this chance meeting opens for her family in these lines:

“The man speaks and it is the sound

of morning birds. My children wave

to him, point to his lamb.

I am tired of dry seeds and praying

for the clouds to tell their story.

I’ve had my fill of beatings,

carrying the elders’ water in clay vessels.

Whatever this man wants, I will give him,

and my children will eat.”

In another poem entitled “Field Flower,” a woman nurtures her dead sister’s son, who is growing up with a gentle nature, not valued by the men of the tribe. The speaker expresses her love for the sweet boy and the fears she harbors for his fate:

“He pets and pets the babies, waters

elders and the sick, hides from storms.

His father? The other men?

They whip any dog that cannot run.

any boy that will not kill.”

In one of the most powerful poems from this chapbook, a character called “Gray Braid” describes how a warring tribe attacks her village, killing her grand daughter and her sister, leaving her near death, but surviving to tell the story:

“I am the shade

of a tree with many circles

and when I am stronger

there will be much to tell.

I am my sister’s tongue.

I am my sister’s tongue.”

Jeanne Bryner is indeed her sister’s tongue, telling a tale of survival, love and perseverance for those whose tongues have been cut out for fighting back against a world of violence and fear. She is a nurse by profession and a poet by avocation whose poetry has been adapted for stage.

Her writing accolades include fellowships from Bucknell University, the Ohio Arts Council, and Vermont Studio Center. Her poetry collection

Smoke:Poems received an American Journal of Nursing 2012 Book of the Year Award. She lives with her husband near a dairy farm in Newton Falls, Ohio. You can find a link to

Early Farming Woman at

WVXU.org/aroundcincinnati

The over-arching themes of Linger to Look seem to be desire, belonging, transformation, and loss. Many of the poems are spoken in the voice of a woman who longs to dance and break free from the bonds that tether her to dusty reality. Horse, bird, water, and stone images abound. Musical use of language led me to finally read many of the poems aloud to myself to further experience the poet’s skill with sound.

The over-arching themes of Linger to Look seem to be desire, belonging, transformation, and loss. Many of the poems are spoken in the voice of a woman who longs to dance and break free from the bonds that tether her to dusty reality. Horse, bird, water, and stone images abound. Musical use of language led me to finally read many of the poems aloud to myself to further experience the poet’s skill with sound.